Andrew Carnegie Distinguished Lecture on Conflict Prevention in Honor of David Hamburg (Video)

Event Details

- Date:

- Friday, November 3, 2017

12:30 AM - 2:00 PM - Location:

-

University Club

1 West 54th St

New York, NY

- Event type

- Conference

Event Transcripts and Video

Noel Lateef: I'm Noel Lateef, President of the Foreign Policy Association and I'm delighted to welcome you this afternoon to the Andrew Carnegie Distinguished Lecture on Conflict Prevention in honor of David Hamburg. We are truly honored to have David Hamburg with us today. David is a visionary and his work on conflict prevention is having a global impact. I can think of few individuals who have made a greater contribution to a more peaceful world. David, you have our admiration and gratitude.

We are joined today by David's successor, as President at the Carnegie Corporation of New York, Vartan Gregorian. Vartan is one of this country's great public intellectuals and we are honored that he is with us today. I want to acknowledge our director, Daisy Soros, whose support for educational opportunities for some of our best and brightest in this country, is truly inspiring. Thank you, Daisy, for your good work.

There are many distinguished diplomats in the room. I would like to welcome Jan Kickert, Permanent Representative of Austria to the United Nations; Ambassador Ib Peterson, Permanent Representative of Denmark to the United Nations; Ambassador Jurgen Schulz, Deputy Permanent Representative of Germany to the United Nations; Ambassador Juan Jose Camacho, Permanent Representative of Mexico to the United Nations; Minister Counselor [Sun Myung 00:02:01] with the Republic of Korea Mission to the United Nations; and from the Consular Corps, we're delighted to welcome the new Consul-General of Australia to the United Nations, Alastair Walton. Of course, this is in alphabetical order of country. The Consul-General of Canada in New York, Phyllis Yaffe; Ambassador Vasilios Philippou, Consul-General of the Republic of Cyprus in New York; and of course, Ambassador Gheewhan Kim, Consul-General of the Republic of Korea.

We are here because of another visionary. Secretary William Perry, who received the Foreign Policy Association medal some years ago, his insights into the situation on the Korean peninsula could not be more timely. We appreciate very much that he has traveled all the way from California to deliver this important lecture. We want to thank him for bringing the California weather with him. And I do want to extend a special welcome to all the Californians who are in the room with us today. Robin Perry, Eric Hamburg, Paula and Bob Reynolds. Secretary Perry will speak after lunch. Bon appetit.

I'm Noel Lateef, President of the Foreign Policy Association and I'm delighted to welcome you this afternoon to the Andrew Carnegie Distinguished Lecture on Conflict Prevention in honor of David Hamburg. We are truly honored to have David Hamburg with us today. David is a visionary and his work on conflict prevention is having a global impact. I can think of few individuals who have made a greater contribution to a more peaceful world. David, you have our admiration and gratitude.

We are joined today by David's successor, as President at the Carnegie Corporation of New York, Vartan Gregorian. Vartan is one of this country's great public intellectuals and we are honored that he is with us today. I want to acknowledge our director, Daisy Soros, whose support for educational opportunities for some of our best and brightest in this country, is truly inspiring. Thank you, Daisy, for your good work.

There are many distinguished diplomats in the room. I would like to welcome Jan Kickert, Permanent Representative of Austria to the United Nations; Ambassador Ib Peterson, Permanent Representative of Denmark to the United Nations; Ambassador Jurgen Schulz, Deputy Permanent Representative of Germany to the United Nations; Ambassador Juan Jose Camacho, Permanent Representative of Mexico to the United Nations; Minister Counselor [Sun Myung 00:02:01] with the Republic of Korea Mission to the United Nations; and from the Consular Corps, we're delighted to welcome the new Consul-General of Australia to the United Nations, Alastair Walton. Of course, this is in alphabetical order of country. The Consul-General of Canada in New York, Phyllis Yaffe; Ambassador Vasilios Philippou, Consul-General of the Republic of Cyprus in New York; and of course, Ambassador Gheewhan Kim, Consul-General of the Republic of Korea.

We are here because of another visionary. Secretary William Perry, who received the Foreign Policy Association medal some years ago, his insights into the situation on the Korean peninsula could not be more timely. We appreciate very much that he has traveled all the way from California to deliver this important lecture. We want to thank him for bringing the California weather with him. And I do want to extend a special welcome to all the Californians who are in the room with us today. Robin Perry, Eric Hamburg, Paula and Bob Reynolds. Secretary Perry will speak after lunch. Bon appetit.

Lunch is served

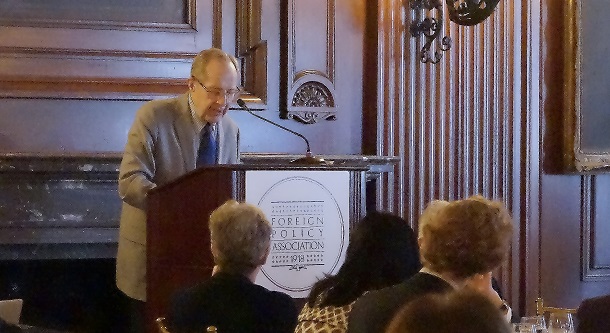

Noel Lateef: Secretary Perry served as the 19th Secretary of Defense of the United States. He previously served as Deputy Secretary of Defense and is Undersecretary of Defense for Research and Engineering. He currently serves on the Defense Policy Board, the International Security Advisory Board, and the Secretary of Energy Advisory Board.

Secretary Perry is a senior fellow at the Hoover Institution and the Freeman Spogli Institute of International Studies. He's a Michael and Barbara Berberian Professor at Stanford University and serves as Co-Director of the Nuclear Risk Reduction Initiative and the Preventive Defense Project.

His most recent book, My Journey at the Nuclear Brink, is a continuation of his efforts to keep the world safe from a nuclear catastrophe. It sets out eloquently his coming of age in the nuclear era, his role in trying to shape it and contain it, and how his thinking has changed about the threat these weapons pose. Ladies and gentlemen, please join me in welcoming secretary William Perry.

William Perry: "In the nightmare of the dark, all the dogs of Europe bark, and the living nations wait, each sequestered in its hate." These prophetic lines were written on the eve of World War II. In the next six years, the nightmare of the dark resulted in the death of more than 50 million people.

When World War II ended in 1945, with the dropping of the atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, the world wanted to believe that the nightmare was finally over. By 1950, the Cold War was well underway, and now the nuclear bombs that ended World War II posed a new kind of nightmare. At the height of the Cold War, a nuclear exchange between the United States and the Soviet Union would have led to hundreds of millions of deaths. Indeed, such a war threatened no less than the end of civilization.

Leaders of our two nations understood that and developed a strategy called Mutual Assured Destruction, aptly called MAD, to try to prevent this catastrophe. MAD did, in fact, work, but it was exceedingly dangerous, and more than once nearly led to a nuclear catastrophe. In particular, we came very close to a civilization ending in catastrophe during the Cuban Missile Crisis.

Have we forgotten the Cuban Missile Crisis? I will never forget it. I was there, part of a small team that worked on into the night, analyzing the data collected that day. By midnight, we'd prepared a report for President Kennedy to guide his judgment and decisions that next day. I know exactly what was going on. Indeed, every morning, when I went into our analysis center, I believed would be my last day on earth.

After the crisis, President Kennedy said that he believed there was one chance in three of that crisis ending in a nuclear catastrophe. In fact, Kennedy's assessment was optimistic. It was optimistic because he did not know, which we now know, that the Soviets already had operational tactical nuclear missiles in Cuba.

Had Kennedy accepted the unanimous recommendation of his Joint Chiefs of Staff and invaded Cuba, our troops would have been decimated on the beachhead and a general nuclear war would surely have followed. We missed that fate simply because Kennedy did not accept that recommendation.

I want to stress that neither Kennedy nor Khrushchev wanted a nuclear war. Indeed, they did everything they could to prevent it, but, in fact, it was largely out of their control, and we almost blundered into a nuclear war. I want to hit that word "blunder" hard because we're coming back to it.

I believe we avoided that catastrophe as much by good luck as by good management. Today, because of the ongoing hostility between the United States and Russia, we are recreating the conditions of the Cold War, conditions that could cause today's leader to blunder into a nuclear war.

We could also blunder into nuclear war by accident, if our missile alert warning system registered a false alarm. How likely do you think that is? How likely?

During the Cold War, there were three such false alarms in the United States that I know about, and two that I know about in the Soviet Union, maybe more. If we take only those five, that comes down to about one in every eight years. I personally experienced one of the false alarms in the United States, and it changed forever my way of thinking about nuclear dangers.

It occurred in October of 1979, when I was the Undersecretary of Defense for Research and Engineering. I was awoken from a sound sleep at 3:00 in the morning. As I sleepily put the phone to my ear, the voice on the other end identified himself as the watch officer at the North American Air Defense Command.

The general got right to the point. He told me that his computer was showing 200 ICBMs on the way from the Soviet Union to the United States, 200 on the way. For one heart-stopping moment, I thought we were about to experience the catastrophe that we had narrowly avoided in the Cuban Missile Crisis, but the general quickly added that he had already concluded that this was a false alarm.

It should have occurred to me earlier. Why was he calling me? I was in charge of research and engineering. I was not in the chain of command. He was calling me because he was wondering what the hell had gone wrong with his computers, and he hoped I could help him discover that.

In fact, during the time I was undersecretary, there were two such false alarms. One of them resulted from a faulty chip in the NORAD computer. The other was a result of human error.

When the computer operators changed shift that night, the new operator mistakenly put in a training tape instead of the operating tape. The training tape, of course, was made to look like a very realistic attack. Our system, with all of its safety features, was still vulnerable to a single person erring, or a single computer chip failing, potentially bringing about the end of our civilization.

Two things, only two things, saved the world from that fate. First of all, the context for the attack was benign. Those accidents occurred at a time when nothing was going on in the world that suggested there might be an attack. Second, more importantly, I think, the watch officers in those two nights were exceptionally thoughtful and responsible. Had they not been, none of us would be here today.

But what if either of those false alarms had occurred during the Cuban Missile Crisis, or during one of the Mideast Crisis where we were on high military alert? In such a context, the watch officer surely would've passed the alarm on to the president, who, after being alerted, would have less than 10 minutes to decide whether to launch our ICBMs before they were destroyed in their silos.

Had he ordered the launch, there would've been no way of recalling the missiles or destroying them in flight. The president would have blundered into a nuclear war. Well, humans will err again. Machines will malfunction again. We will have more false alarms.

I would like to tell you that there's a sequel to the story, that when we recognized the level of catastrophe that could result in a false alarm, we decided to drop our launch on warning policy as being too dangerous, but, of course, that did not happen. Russia and the United States both still have a policy of launch on warning. Both Russia and the United States are building new ICBMs to replace the ones they used during the Cold War.

This means that the future of our civilization will depend on the judgment of an American or a Russian watch officer in deciding whether or not to pass an alert to the president. If he does pass it on, it would depend upon the judgment and temperament of Vladimir Putin or the judgment and temperament of Donald Trump.

When the Cold War ended in 1989, the world breathed a huge sigh of relief. We had somehow dodged the bullet, a bullet that could have extinguished our civilization. But in the last decade, inexplicably, inexplicably to me, we are beginning a new Cold War.

The dogs of Europe are barking again, and not just in Europe. Today's nightmare is that the barking will escalate into a nuclear war; the worst case being a nuclear war between the United States and Russia. How likely is that?

I must start off by telling you that I am a Russophile, a Russophile. I have visited Russia more than 30 times. I led four Stanford study tours to Russia. I love Russian music, Russian literature, and Russian art. I've many Russian friends, some of them dating back to the Cold War era, but I must tell you I am very concerned today. US-Russian relations are comparable, they're comparable to the dark days of the Cold War. How could we have let that happen? How could anybody who have lived through the Cold War want to live through another one?

After the Soviet Union dissolved, there were turbulent times in Russia. There's a very real possibility of major disorder, even a major civil war. I give great credit to the Russian people who somehow got through that period without major bloodshed. But Russia did enter a period of economic collapse and serious governmental abuse, particularly in the privatizing of state-owned properties.

The '90s are sometimes called by the Russians as the Decade of Humiliation, the Decade of Humiliation. During that period, some Americans recognized that the turbulence in the former Soviet Union posed a special danger to all of us as a consequence of the 4,000 nuclear weapons left in Ukraine, Kazakhstan, and Belarus after the Soviet Union collapsed.

Foremost among those Americans was David Hamburg, then the President of the Carnegie Corporation. He not only recognized the danger of those loose nukes, he acted vigorously to deal with it. He organized a fact-finding trip to Russia and Ukraine to determine whether the loose nukes problem was, in fact, real.

On that trip, beside David, were two far-sighted senators, Sam Nunn and Dick Lugar ... God knows, I wish we had two of them in the Senate today ... and two of David's advisers, myself and Ash Carter. Our findings were unambiguous. The danger was even greater than had been reported.

On the airplane ride home, we drafted what was soon to become the Nunn-Lugar Program, which authorized the secretary of defense to assist in those nations in dismantling the 4,000 nuclear weapons on their territory. A year later, to my surprise, I found myself as secretary of defense, with the responsibility of executing the program that I had helped David to create, and with Ash Carter as my assistant secretary.

We soon discovered that it was far easier to recommend than it was to execute, but I did make it my top priority. In three years' time, we did dismantle those 4,000 nuclear weapons, as well as an additional 4,000 in the United States. That was the Nunn-Lugar Program and that was its result.

During that same period, and again with the help and encouragement of David Hamburg, I worked to foster positive relations with the Russian military. I brought the Russian minister of defense into NATO meetings. He sat right beside me in the NATO meeting. I formed the Partnership for Peace, whereby former Warsaw Pact nations could participate with NATO in joint peacekeeping military operations.

I negotiated with the Russian minister of defense to have a Russian brigade part of an American division, reporting to an American general during the Bosnia peacekeeping operation. That period, undoubtedly, was a high point of US and Russian relations, and proved that it could be done. I give much of the credit for that to David Hamburg.

When I left the Pentagon in 1997, I believed that we were well on our way to ending the Cold War enmity between the US and Russia forever, but that was not to be. In the late '90s, the downward slide started in the first instance as a result of actions taken by the United States. Let me repeat that. In the first instance by actions taken by the United States. Under US leadership, NATO expanded its borders to the borders of Russia. I had vigorously opposed this as secretary of defense, but obviously lost the battle.

In the next decade, the United States installed a ballistic missile defense system in Eastern Europe, which I had prevented when I was secretary of defense since I knew that Russia saw it as a threat to their deterrence. Perhaps most importantly, this past decade, the United States has supported color revolutions in the Mideast and in Ukraine. When Putin regained the presidency and experienced large groups of protesters in Red Square, he blamed the United States for organizing that and he saw it as an attempt by the United States to overthrow his regime.

The hostility in our relationship today was stimulated partly by actions of the United States and NATO, but it was also stimulated by aggressive actions and statements made by Putin. He wanted to restore some of the power and the territory of the former Soviet Union, or, to put it another way, he wanted to make Russia great again. He wanted to strike back at the United States for the actions we had taken at the turn of the century.

I'm especially concerned about Russian actions in the nuclear field. Putin dropped Russians' long-standing policy of no first use of nuclear weapons. In fact, he implied that nukes would be the weapon of choice if Russia were threatened. He annexed Crimea and supported separatist movements in Ukraine.

He threatened his neighbors in Europe with nuclear missile, the Iskander missile, based in Kaliningrad. He indirectly threatened the United States when his head of media publicly proclaimed that Russia is the only nation capable of turning the United States into radioactive ash.

Most worrisome, Putin has made rebuilding the Cold War nuclear arsenal its highest security priority. Of course, the United States is following his lead. Have we forgotten the cost and the dangers of the Cold War nuclear arms race, which we are about to redo again?

Just last week, the Congressional Budget Office reminded us of the costs by releasing its estimate that the cost of the United States rebuilding and operating a nuclear arsenal would be $1.2 trillion. Most people can't relate to a number like $1.2 trillion. It's a big number, though, I assure you.

These costs will cause serious problems to the American budget in the next few decades, but the problems to the Russian budget will be even greater, because when Putin started his big arms buildup, oil was riding at $100 a barrel and higher. The Russian economy was booming as a result of that, what the oil revenues were providing. It provided a significant part of his military funding and the socialist programs upon which much of his popularity today rests.

At $30 to $50 a barrel, current prices [inaudible 00:19:24] the last year or two, the Russian government has been eating into its cash reserves, and Putin soon might have to choose between guns and butter, even as Trump's budget proposals imply that Americans can have both. The budget problems in the new arms race are serious for both of our nations, but the national security problems, I fear, are even greater.

Having said that about Russia, let me make three brief comments about three other nuclear dangers in the world today. I would discuss these very briefly. First of all, nuclear terror attack against Washington, against New York, against London, against Moscow. Secondly, North Korea using nuclear weapons against South Korea or Japan. Third, a regional nuclear war, for example, between India and Pakistan.

I'm going to make only two points about a nuclear terror attack. The first is it's much more likely than most people understand and, second, the consequences of such an attack will be much more serious than most people understand. Indeed, the damage could entail not just 100,000 or so casualties, but economic, social, and political problems that are enormously destructive.

We face an even greater danger with North Korea's arsenal, presently consisting of about 20 to 30 nuclear weapons. I believe the North Korean leaders built their nuclear arsenal in order to keep their regime and power, and that they will not use it in an unprovoked attack against South Korea, Japan, or the United States. They know that this would lead to their own death and the end of their regime.

The North Korea is not Al Qaeda and it's not ISIS. They're not seeking martyrdom. They're seeking to stay in power. Their nuclear arsenal is useful, but only if they do not use it.

The danger of a North Korean nuclear arsenal is not an unprovoked attack, but that we will blunder, we will blunder into a military conflict, which will then escalate into a nuclear war. Unfortunately, the inflammatory rhetoric between the American and North Korean leaders creates the environment which makes such a blunder all too likely.

To put that in perspective, North Korea's nuclear arsenal today has the capability of destroying Seoul and destroying Tokyo. We're talking about 10 million deaths perhaps. Having given you that good news, let me switch to South Asia.

India and Pakistan, as you know, have had three major wars since partition. The basic cause of the war, the ownership of Kashmir, is still unresolved. Since these three wars, India and Pakistan have each built nuclear arsenals, which today have almost 200 nuclear weapons in each country, and they continue to build.

A fourth India-Pakistan war, in my judgment, would likely go nuclear. I'm going to show you a brief video that dramatizes a hypothetical scenario of how such a war might start and what its likely consequences would be. With good luck on the technical side, we're going to see a four-minute video dramatizing an India-Pakistan war, if this will make it plain much more than any words I can say.

Video Narration: In November of 2008, terrorists based out of Pakistan attacked the Taj Mahal Hotel and other targets in Mumbai, India, killing 168 and wounding hundreds more. I vividly remember as the scenes of horror played out on television for four days in front of a stunned worldwide audience.

Despite allegations of Pakistani military involvement in the attacks, the situation did not escalate into a military conflict that time, but what if something like that happens again? I cannot help but imagine a darker outcome. My name is William Perry, and what follows is my South Asia nuclear nightmare.

On the early morning of January 26th, members of a Pakistani militant group prepare for an attack on the Republic Day Parade celebration in New Delhi. The attack claims over 300 lives, injuring countless others. All the militants died during the attack, except one.

Upon interrogation, he reveals the location of the group's hideout. The information is quickly passed to senior government officials, and the Cold Start response is initiated. It gives the Indian military authorization to launch a punitive raid against the militants and cross over the border from the Punjab into Pakistani territory.

In anticipation of India's invasion, the Pakistani government orders the Nasr mobile short-range tactical nuclear weapon system to be deployed to the border. The UN convenes an emergency meeting and urges both sides to show restraint.

Just before dawn, the Indian Army quickly overwhelms the militant camp. However, most of the fighters have already fled deeper into Pakistan. As the Indians ponder their next course of action, the Nasr system is moved near the border, 10 miles north of Kaswal. Knowing that Pakistani military doctrine authorizes the use of tactical nuclear weapons against any invading force, the move is perceived as an urgent threat by the Indian military.

After tense consultations, the government authorizes an air strike to disable the nuclear battery. Despite the use of conventional munitions in the air strike, the intense bombardment causes one of the warheads to detonate. The nuclear explosion causes massive damage around the suburbs of Lahore, along with villages on both sides of the border. Military and civilian casualties are in the tens of thousands.

Unable to identify the source of the nuclear explosions, Pakistan interprets them as a nuclear first strike from India. In response, the Pakistani military launches nuclear missiles and dozens of military and civilian targets in India. Minutes later, India orders a counterstrike.

27 major cities were completely destroyed. Casualties are in the tens of millions. Both governments collapsed and the militaries take control. The radioactive fallout reaches as far as Australia. The radiation also saturates the Himalayas, contaminating freshwater for over a dozen countries, including China. The smoke and ash dispersed in the atmosphere lowers temperatures across all of Asia. Crop failures lead to food shortages around the globe, resulting in widespread starvation. Billions of lives are affected.

William Perry: A nuclear war in Korea, or Pakistan-India nuclear war, could entail deaths comparable to all of the deaths in World War II, except they would occur in six hours instead of in six years. In some, I believe the danger is some sort of a nuclear catastrophe. Today is greater than it was during the Cold War, and the consequences would be more terrible than World War II. But most people, including our political leaders, are blissfully unaware of this. Therefore, our policies do not reflect the dangers.

In a small way, I'm trying to deal with this problem. I've written a book, My Journey at the Nuclear Brink, to educate the public on nuclear dangers we face today and policies that could lower those dangers. The book is now in English, Chinese, Japanese, Korean, and Russian.

I'm trying to educate the public through this book, through lectures, and through courses, but I understand this message needs to get across not to tens of thousands, but to tens of millions. Books and lectures and courses do not do that, so I moved to the internet in trying to get this message across.

I've setup a website, the wjperryproject.org website. I have YouTube videos on this. I've prepared two of them, but you've seen one today. I'm particularly interested in emphasizing educating youth on this problem. These are on YouTube, and there'd be more of them on YouTube coming.

I've started online courses. Of course, at Stanford, it's a heavily attended course. You get 300 people, which is good. I want to get this message across to 300,000 people, more than that, so we have created something called MOOCs, Massive Open Online Courses. Two of those have been done. The second one just started a few weeks ago.

The second, by the way, if you want to take that course, you can do so. It's free. It's a Stanford free course. This one is focused on the issues of nuclear terrorism. You go to wjperryproject.org, press the button, and you can sign up for that course and take it without grades and without cost.

This MOOC, by the way, this online course, was sponsored by Carnegie. Vartan Gregorian's here today and Diana's here today. I want to thank them for that. This is the new way of trying to get the message across to younger people, through online videos.

I would be the first to admit that educational programs, even video educational programs, even online courses, seem like a feeble response to such a daunting problem, but the consequences of a nuclear war are so terrible that everyone should do what they can do. I'm doing what I can do by devoting the remainder of my career to this mission.

I do this because I promised myself that my eight grandchildren and my three great-grandchildren will not have to lead their life as I led mine, with the threat of nuclear extinction hanging over my head like a dark cloud every day. That is my promise to them.

Even though I'm well past retirement age, I will do everything I can to keep that promise, or, in the words of Robert Frost: "The woods are lovely, dark, and deep, but I have promises to keep and miles to go before I sleep, and miles to go before I sleep." Thank you. Noel, do you want to have questions?

Noel Lateef: Sure. Secretary Perry has very graciously agreed to take some questions. Thank you for those very sobering and insightful remarks. There is a mic. We'll start with Jonathan Granoff.

Jonathan Granoff: Secretary Perry, you are an inspiration to many of us, so I want to thank you for that inspiration. I also want to thank Mexico and Austria, which led in obtaining a treaty to prohibit nuclear weapons, recently voted at the United Nations. 120 countries voted in favor of that treaty. I regret to say that neither the United States nor Russia even attended that process.

I know that you're on the cutting edge of addressing those issues, and there's two initiatives that I wanted you ... You would comment on. One is the joint enterprise that is in the book by George Shultz and Ambassador Goodby, the joint enterprise, the other is the concept of a crisis center to create an ongoing center to address the potential misunderstandings between Russia and the United States.

William Perry: I think both of those are very important, both of them making very slow headway. Again, I think because of the problem of education. I must say, though, when young people, who when they hear me talk on this subject, say, "What can I do? What can one person do?" I now have, I think, an answer: I point to what has been done in this initiative. Whereas as I understand, the UN resolutions largely passed through the lobbying and the energy of the young people who are supportive. Maybe the ambassador has something to say about that. Would you want to comment on that? Is that a correct statement, or ... Yeah. I point out to them, "Here is an example of what not one young person could do, but one young people in conjunction with many of his compatriots could do." Thank you for that example.

Noel Lateef: Ambassador Jan Kickert right here.

Jan Kickert: Thank you very much, Secretary.

Noel Lateef: There's a microphone.

Jan Kickert: Oh. Thank you very much, Secretary. I think you're right. The dedication of the Peace Prize, the Nobel Peace Prize, to ICAN, to a civil society organization is proof to what you just said, which is a network of civil society organizations all over the world and driven by young people in particular.

If you look at the representatives of ICAN, these are young people who just see what most of us in our generation having gone through the Cold War don't see, that nuclear weapons are an existential threat to humankind, where we don't have this knowledge spread around so that the people have the conscientiousness that this is, as climate change, something which would just rid our planet of humanity.

What you described is what we have experienced in conferences on the humanitarian consequences of nuclear weapons in Nayarit, Mexico and also in Vienna, which was motivating us to strive for this treaty prohibiting nuclear weapons. Of course, we know that it is us, the non-nuclear weapon states, who cannot disarm the nuclear.

My question would be to you why are the nuclear weapon states so vehemently, ferociously working against our treaty, putting pressure on every state of this world not to sign up to it? The second question is how can we convince the nuclear weapon state that nuclear disarmament is the only way not only for their own security, but the survival of humankind? Thank you.

William Perry: Yeah. I cannot answer that question directly. I can say that some of the scholars I've talked to who are not in favor of the treaty have argued that it would take the emphasis away from smaller measures that can be taken right now. For example, in the review conference of the NPT, they say that it would drive a wedge between the monopoly of the amendment, compromise solutions.

I reject that, but that's what they're saying. My view is it's important to make a strong moral and ethical statement that we ought to get rid of nuclear weapons. When people say, "But nothing is happening because of this statement," I will give one example, which is when the United States stated that all men are created equal, when they stated that, we had slaves, women couldn't vote. You couldn't vote unless you own land.

They were not created equal, but it was a statement of principle, it ought to be all men ought to be created equal. Over the years, sometimes with great hardship, we've moved closer and closer to that goal. We're not there yet, but at least we're moving in the right directions. A statement of a moral principle is worth making, even it did not have immediate results.

Noel Lateef: Susan Perkins over here.

Susan Perkins: I don't know how many of you know that one of the topics, the eight topics, for this year's 2017 Foreign Policy Association, Great Decisions Program's discussion groups, is about nuclear security. I would recommend to all of you that you can go online, look at greatdecisions.org or FPA.org, put /greatdecisions, and you can see that the Foreign Policy Association ... You can read about that program, but you could also see it's one of the eight programs, that each year the FPA picks out eight topics that should be talked about.

They create a half-hour film, they have a Briefing Book, and they form discussion groups all over this country, and I think they should do them all over the world. They have over 90 of them in this country. We could use more because they're getting people to listen and understand what you're trying to tell people. Thank you very much.

Noel Lateef: Thank you, Susan. Ambassador Camacho of Mexico, please.

Juan Camacho: Thank you, Mr. Secretary, for your words. Of course, I couldn't agree more with you. I also agree entirely with my colleague, the Austrian Ambassador Jan.

Two probably very technical questions that you could clarify to us. One is how real, technically speaking, is the North Korean threat to the US itself? They claim that they can launch a missile that could reach the US. How true is that? Because my understanding is that their missile capability remains still really not there. That's one question.

Second, how likely you see that Japan and Korea becoming nuclear? There was recently a very interesting piece in the New York Times saying that South Korea could build nuclear weapons in six months and Japan in two years. Do you see that actually happening? Thanks so much and, really, congratulations for your work. Thank you so much.

William Perry: The first question, the technical threat from North Korea is very real indeed. They have 20 to 30 nuclear weapons, they have hundreds of missiles. They can launch those weapons today against South Korea, against Japan. Within a year or two, maybe they'll be able to launch against the United States.

The technical threat is real. As I said in my talk, though, in reality, they're not going to do this because deterrence does work. They're not suicidal. They're not seeking martyrdom, so they're not going to do it.

The danger then is that we will do something or say something which will precipitate some sort of minor conflict, which would then escalate into a nuclear conflict. I say, again, the environment that makes such a blunder likely is this inflammatory rhetoric between their leader and our leader, threatening to put their country out, destroy their county with fire and fury.

On the other side, North Korea is saying they're going to turn Seoul into a sea of flames. This kind of rhetoric, I think, creates an environment in which some kind of an accident or blunder is all too likely. That's the danger, not that they're going to fire an unprovoked fire against us. The other question had to do again with? You had a second question.

Juan Camacho: The capacity [inaudible 00:42:50] Japan and South Korea [inaudible 00:42:55].

William Perry: Oh. I would only say it's more likely today than it was a year ago, two or three years ago. More people in Japan and South Korea are talking about it today, and some of them are talking seriously about it.

My best judgment is they will not go nuclear. That does hinge, to a certain extent, on the United States being very, very clear that we do not want to go nuclear and that our extended deterrence is there and they can have 100% confidence in it. But had you asked me that question three years ago, my answer would have been no. Now I have to qualify the answer, which doesn't make me too happy.

Noel Lateef: Secretary Perry, thank you very much for being with us today. I really appreciate it.

William Perry: Thank you.

Introduction

William J. Perry

Upcoming events in this area

- Title

- Location

-

-

FPA's Elbrun Kimmelman Distinguished Lecture on U.S.-India Relations

Apr 30, 2024

-

New York , NY

-

-

-

FPA 2024 Cultural Diplomacy Dinner

May 9, 2024

-

New York, NY

-